E

D I T

O R I

A L

“April fools”

SOME simply refused to follow, or just

ignore the radical change. Others were entirely innocent of the sudden shift

since communication in those times is very slow. Hence, both the rebellious and

the innocents were labeled as “fools”. Such

was the folkloric story making April 1 as “April Fools Day” with the reform of the Julian Calendar around 1582 in France under King Charles IX. Then reigning

Pope Gregory XIII introduced said reform moving new year’s day from March 25 to

April 1 [onset of new year’s week]; then

finally to January 1 as new year’s

day in the succeeding Gregorian Calendar of

today.

Asingan’s town fiesta for

decades—even way before the Marcos era—has always been observed on the last

week of April past the holidays to provide common time space for “vacacionistas” both locals and “balikbayans” to bond together for the traditionally long summer

break. Most students were on furlough while workers normally file their

vacation leave to join the summer festivities.

Not necessarily so these days. Confusion

marred the vacation schedules of people coming from within and out of the

country when the neophyte administration of Mayor Heidee Chua moved the fiesta

period up unto the second week of April 2011 for no apparent reason than her

own. For the town’s 2012 fiesta, it jumped into the third week of the month. Will

it move again on 2013, an election year?

Politicking around here is rather

fast-pace; fast-tracked rather too early; and

rather messy than it used to be. Again, for no apparent reason than the

politicians’ covert own. Seemed vanished to thin air were the promises of

delivering Asingan from being a Class C municipality to Class A, with a view to

making it a City.

Aside from being the onset of the

year in olden times, April of today is recognized as Earth Month with April 22 specifically designated as Earth Day. As lovers of our only home

planet, Asingan NewsLine urges both

Asinganians and the Filipino people around the globe to protect and conserve

mother earth before SHE falls and fails to protect and feed us all. We disdain

pollution as killing the earth in the same manner that we curse politics as

prime pollutant to the socio-physical environment of this bungling nation

called Pinas.

Nope… We refuse to be duped. April fools we’re not! eb . anl

N e w s L i n e

a. Asingan holds April 2012 fiesta in comic mood

Asingan’s town fiesta 2012 was held this time yet with more

comical change, or so it seems.

A classic purple and velvety “stage within a stage” was built

inside the town plaza to showcase a pageantry that some say turned to be a

religious liturgy of sort. Huge and grandiose it was so-it-must-be-costly, was

the impression of this reporter.

The public saw none of the traditional “Balikbayan Night” but an

edgy and hastily prepared “ASGRA-AMRA balikbayan night” held April 20. Three

emcees were designated up stage but failed to say what is ASGRA-AMRA all about.

Even on write-ups, the authors missed to spell out the strange words. The

organizers were all hosannas to themselves both onstage and in the handouts

distributed to the public. Thanks to them, anyways.

The public saw none of the traditional “Balikbayan Night” but an

edgy and hastily prepared “ASGRA-AMRA balikbayan night” held April 20. Three

emcees were designated up stage but failed to say what is ASGRA-AMRA all about.

Even on write-ups, the authors missed to spell out the strange words. The

organizers were all hosannas to themselves both onstage and in the handouts

distributed to the public. Thanks to them, anyways.

Oh, some curious souls note not a name of the Vice-Mayor in any

fiesta literature this time!

And yes, the fiesta period was moved from last year’s second week

to the third week of April this year. In

older times, the town fiesta stays on the fourth week of April.

How about moving it to May 1—Labor Day—to signify the laboring character

of the Asinganian!? We luv ‘ya old fools!

–liberatojose@yahoo.com

b. RA Class

’68 Alumni Association meets anew

A special follow-up gathering was slated for April 29, a

picnic-meet and bonding of sort at Viring Lopez-Jover’s place in Domanpot to

mark the first year anniversary of last year’s first ever grand

reunion-homecoming in 43 years of the RA Class ’68.

In town to grace both affairs is Rudy Antonio, Co-Chair for

External Affairs of RA Class ’68 Alumni Association who arrived home to Pinas

from Vancouver, BC with better half Evelyn last April 18.

Come one, come all! –lalin layos-pascual &

rodnellayco@yahoo.com

F E A T U R E

“Small

world!”: Rizal Academians invade Boracay

on e-day

Reports from: Rudy D. Antonio, Vancouver

Correspondent/Ruben M. Balino, ANL Editor

“LEAST expected and so sudden!” utters

the stunned and unsuspecting host. “What

a small world!?” chorused the visiting party.

The visiting

party in this case are townmates and high school buddies at the now defunct

Rizal Academy whose by-lines appearing above were accompanied with report-stories

they filed for Asingan NewsLine while

touring Boracay April 21-23 both for job and leisure in

the company of their private counsels Evelyn and Wena.

“What

brought you here.., and how!?” interjects the surprised Ms. Josefina Padilla-Salme, herself

a product of Rizal Academy-Class ’71 and a native of Barangay Ariston Este back home in Asingan,

Pangasinan. “Josie”—as she is fondly called around Boracay—is married

to the mild-mannered gentleman Diony Salme from Dumaguete City. “Marriage took

me here in Boracay in 1975 where Diony was then working with the Elizalde’s

since 1974,” she says matter-of-factly. The couple now owns the Diony’s Resort

and Restobar—one of the pioneers and more classic resorts in Boracay island in

the Visayas.

While on

breast walking along the eastside shore of the shoe-shape island resort, we

dropped by Diony’s early morning April 22 for the hasty and brief “kumustahan

blues”; then get back late afternoon of the same day for the lengthy sequel

that lasted past nine evening and wandered back to yesteryears—on peoples,

places, and events.

“Events

hereof in Boracay as of late and in recent years were less desirable to say the

least,” confides one local tourist interviewed by ANL at nearby Surfside Resort. No scientific study is needed to

come out with hi-tech EIA’s [environmental impact assessments] to prove such

fear. “Can stroll around the island and your eyes can catch it all. Quite

different now than two decades ago,” confirms Josie.

“Events

hereof in Boracay as of late and in recent years were less desirable to say the

least,” confides one local tourist interviewed by ANL at nearby Surfside Resort. No scientific study is needed to

come out with hi-tech EIA’s [environmental impact assessments] to prove such

fear. “Can stroll around the island and your eyes can catch it all. Quite

different now than two decades ago,” confirms Josie.

The most

visible proofs of course are the houses dotting most parts of the island like

mushrooms and the roads crisscrossing all over like in a typical subdivision.

The former island paradise of hilly-to-mountainous terrain now looks more of an

urban residential-commercial site combined. This aside from past studies on the

deteriorating condition of the waters around the island. Not a few say that

foreigners, the affluent and influential rich showed the way in the

despoliation of the island from 1979 into the peak ‘90s.

So what’s

the fuss about it? None in our narrow selfish interest and fragmented outlook.

None in our shallow intellect, scared wit and blurred consciousness. None in

our disoriented and disorganized ranks. None if we won’t rise up from slumber.

On Earth

Day, we can’t afford to have none to offer mother earth. Otherwise, we will be

reaping none in the unsettling future.

P U N C H L I N E

Busting

the Forest Myths:

People as Part of the Solution

People as Part of the Solution

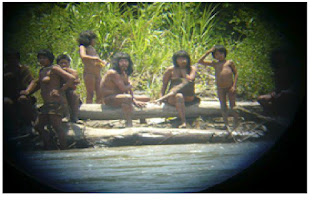

The

long-held contention that rural forest communities are the prime culprits in

tropical forest destruction is increasingly being discredited, as evidence

mounts that the best way to protect rainforests is to involve local residents

in sustainable management.

by fred pearce

Some forest campaigners have been saying it for years, but now they have the research to prove it: Local communities are the most effective managers of their forests, best able to combine sustainable harvests with conservation.

A series of studies unveiled in the past year have skewered the long-held view — still espoused by many governments and even some in the environmental community — that poor forest dwellers are the prime culprits in deforestation and that the best conservation option is to combine strict ecosystem protection in some areas with intensive cultivation elsewhere.

Here are seven myths punctured by recent research.

Myth One: Forests prevent short-term rural wealth generation. Forest communities therefore have an economic incentive to get rid of them and replace them with permanent farms. Forest protection requires curbing them.

Reality: A six-year global study of forest use, deforestation and poverty conducted by the Indonesia-based Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) has found that harvested natural resources make up the largest component of incomes from people living in and around tropical forests. Nature contributes 31 percent of household income, more than crop farming (29 percent), wages (14 percent), or raising livestock (12 percent).

Forests emerge from the study — the result of detailed interviews conducted by Ph. D. students at 8,000 households in 24 countries — as important sources of food, firewood, and construction materials that communities want to protect.

Some forest campaigners have been saying it for years, but now they have the research to prove it: Local communities are the most effective managers of their forests, best able to combine sustainable harvests with conservation.

A series of studies unveiled in the past year have skewered the long-held view — still espoused by many governments and even some in the environmental community — that poor forest dwellers are the prime culprits in deforestation and that the best conservation option is to combine strict ecosystem protection in some areas with intensive cultivation elsewhere.

Here are seven myths punctured by recent research.

Myth One: Forests prevent short-term rural wealth generation. Forest communities therefore have an economic incentive to get rid of them and replace them with permanent farms. Forest protection requires curbing them.

Reality: A six-year global study of forest use, deforestation and poverty conducted by the Indonesia-based Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) has found that harvested natural resources make up the largest component of incomes from people living in and around tropical forests. Nature contributes 31 percent of household income, more than crop farming (29 percent), wages (14 percent), or raising livestock (12 percent).

Forests emerge from the study — the result of detailed interviews conducted by Ph. D. students at 8,000 households in 24 countries — as important sources of food, firewood, and construction materials that communities want to protect.

Deforestation rates are substantially higher on lands protected

by the state than in community-managed forests. But this

forest fecundity is largely ignored by policymakers, says Frances Seymour,

CIFOR’s director-general, who presented many of the findings at the Royal

Society in London last June, ahead of publication in peer-reviewed journals.

“This income is largely invisible in national statistics,” she said, because

the produce is either consumed in the home or sold in local markets unmonitored

by national data-collectors.

Myth Two: Deforestation is carried out mainly by the poorest farmers, often as a coping strategy to get through bad times. What they need is economic development to wean them away from the forests.

Reality: The same CIFOR study found that within forest communities it is the rich who take more from the forests. They have the means, wielding chainsaws rather than machetes. But they are also the top dogs, able to assert control of community-run forests. “We see that at the level of households within villages, but also at a national and international level, where deforestation has been faster in Latin America, which is richer,” says Seymour.

The study found that just over a quarter of all households clear some forest each year, with an average take of 1.3 hectares, mostly to grow crops. But the bottom line is that deforestation is usually a source of wealth for the rich in good times, rather than a coping strategy for the poor. In bad times, the poor are more likely to leave the forest in search of wages than to stay and trash the place, says CIFOR principal scientist Sven Wunder.

Myth Three: Forest protection, many governments say, cannot be entrusted to local communities. It is best done by state authorities, perhaps with help from environmental NGOs, on land under the control of the state.

Reality: A recent meta-analysis of case studies found that deforestation rates are substantially higher on lands “protected” by the state than in community-managed forests. There was greater biodiversity in the low-intensity farming area than in primary forest. There are well-known maps showing that the best protected parts of the Amazon rainforest, for instance, are those designated as native reserves, run by the Kayapo Indians and others. This seems to be the rule rather than the exception, Luciana Porter-Bolland, of the Institute of Ecology in Veracruz, Mexico, and others concluded.

When the state is in charge, rules are barely enforced, corruption is frequent, and forest dwellers have little stake in protecting forest resources, because they do not own them. Where the people who live there control the forests, they are much more likely to protect them.

The analysis confirms a global study two years ago by Ashwini Chhatre of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who, with Arun Agrawal, compared data on forest ownership with the carbon stored in forests and found that community forests held more. “Our findings show that we can increase carbon sequestration simply by transferring ownership of forests from governments to communities,” says Chhatre.

Myth Four: Agriculture is bad for biodiversity.

Reality: It sounds like a no-brainer. Of course, intensive farming will wreck forest ecosystems and replace them with monocultures. But traditional farming systems are often bio-diverse, and may take place within forest ecosystems, rather than replacing them. New research in Oaxaca state in Mexico suggests that such farms enhance forest biodiversity.

James Robson and Fikret Berkes of the University of Manitoba investigated the impact of the recent widespread desertion of forests by Oaxaca farmers heading for the cities.

Myth Two: Deforestation is carried out mainly by the poorest farmers, often as a coping strategy to get through bad times. What they need is economic development to wean them away from the forests.

Reality: The same CIFOR study found that within forest communities it is the rich who take more from the forests. They have the means, wielding chainsaws rather than machetes. But they are also the top dogs, able to assert control of community-run forests. “We see that at the level of households within villages, but also at a national and international level, where deforestation has been faster in Latin America, which is richer,” says Seymour.

The study found that just over a quarter of all households clear some forest each year, with an average take of 1.3 hectares, mostly to grow crops. But the bottom line is that deforestation is usually a source of wealth for the rich in good times, rather than a coping strategy for the poor. In bad times, the poor are more likely to leave the forest in search of wages than to stay and trash the place, says CIFOR principal scientist Sven Wunder.

Myth Three: Forest protection, many governments say, cannot be entrusted to local communities. It is best done by state authorities, perhaps with help from environmental NGOs, on land under the control of the state.

Reality: A recent meta-analysis of case studies found that deforestation rates are substantially higher on lands “protected” by the state than in community-managed forests. There was greater biodiversity in the low-intensity farming area than in primary forest. There are well-known maps showing that the best protected parts of the Amazon rainforest, for instance, are those designated as native reserves, run by the Kayapo Indians and others. This seems to be the rule rather than the exception, Luciana Porter-Bolland, of the Institute of Ecology in Veracruz, Mexico, and others concluded.

When the state is in charge, rules are barely enforced, corruption is frequent, and forest dwellers have little stake in protecting forest resources, because they do not own them. Where the people who live there control the forests, they are much more likely to protect them.

The analysis confirms a global study two years ago by Ashwini Chhatre of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who, with Arun Agrawal, compared data on forest ownership with the carbon stored in forests and found that community forests held more. “Our findings show that we can increase carbon sequestration simply by transferring ownership of forests from governments to communities,” says Chhatre.

Myth Four: Agriculture is bad for biodiversity.

Reality: It sounds like a no-brainer. Of course, intensive farming will wreck forest ecosystems and replace them with monocultures. But traditional farming systems are often bio-diverse, and may take place within forest ecosystems, rather than replacing them. New research in Oaxaca state in Mexico suggests that such farms enhance forest biodiversity.

James Robson and Fikret Berkes of the University of Manitoba investigated the impact of the recent widespread desertion of forests by Oaxaca farmers heading for the cities.

This may be no isolated finding. CIFOR’s Christine Padoch said the Oaxaca study showed that “rapid urbanization, simplified agricultural systems and abandonment of local resource-use traditions are sweeping across the forested tropics.”

Myth Five: Illegal local wood-cutters are a major threat to forests. Much better to maximize both production and conservation by curbing local wood-cutters and allowing commercial loggers to take over those forests set aside for “productive” use. Commercial loggers are, it is argued, easier to police and can operate according to strict rules on sustainability, such as those of the Forest Stewardship Council.

Reality: There is a serious downside to this approach. In central and West African countries such as Cameroon, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, and Liberia, small-scale logging by locals is often a much bigger contributor to local economies and employment than large-scale enterprises. Moreover, most lumber harvested by this informal sector is processed locally for furniture and other local needs, whereas large-scale enterprises mostly export the timber as logs.

It is far from clear that the local wood-cutters do more damage than outside loggers. But a study by the Washington-based Rights and Resources Initiative found that they produce more benefits for their local communities, in jobs, income, and products. And, like other local forest users, they may be more amenable to community controls on their activities. Andy White, the coordinator of the initiative, concluded that small-scale forest enterprises “have contributed substantially to equity, forest conservation, and poverty reduction. Supporting their development and suspending public support for large-scale industrial concessions should be key priorities.”

Myth Six: Degraded forest land is a wasteland that should be targeted for high-intensity agriculture such as oil-palm cultivation and timber plantations. Many environmentalists encourage this. For instance, the World Resources Institute is mapping Indonesian degraded lands to help the government there “divert new oil palm plantation development onto degraded lands instead of expanding production into natural forests.”

Reality: This is risky. A study in Borneo, a major biodiversity hotspot, found that, even after repeated logging, degraded forests retain 75 percent of bird and dung-bettle species, which were chosen to represent wider biodiversity. The indiscriminate conversion of these forests to oil-palm and other intensive agriculture is a big mistake, says David Edwards, co-author of the study and now at James Cook University in Australia.‘Natural resource protection can only be achieved if the rights of forest-dwelling people are respected,’ says one advocate. “Degraded forests retain much of the biodiversity found in primary forests. Conservationists ignore them at their peril.”

Myth Seven: To prevent further forest destruction, we urgently need to intensify agriculture. This is often called the Borlaug hypothesis after its originator, the green revolution pioneer Norman Borlaug. He argued that the more we can grow on existing farmland, the less pressure there will be to clear forests for growing more crops.

Reality: The counter-argument is that commercial farmers don’t clear forests to feed the world; they do it to make money. So helping farmers become more efficient and more productive won’t reduce the threat. It will increase it.

Thomas Rudel of Rutgers University in New Jersey compared trends in national agricultural yields with the amount of land planted with cropssince 1990. He argued that if Borlaug was right, then the spread of cropland should be least in countries where yields rose fastest. Sadly not. Mostly, yields and cultivated area rose together, as farming became more profitable.

All this raises vital issues for forest protection. Twenty years ago, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, sustainable development was declared the key to a green and equitable global future. But nobody quite knew what it meant. The UN is planning a follow-up Rio+20 event this June, and the question of what is meant by “sustainable development” will come under intense examination.

L I T E R A R Y